Art in Motion: Léon Bakst, Orientalism and the Ballet Russes

The Ballet as a Fashion Medium

The dancer’s body is a powerful medium for fashion; dynamic movement or choreography as found in ballet has the power to bring a garment to life, allowing the audience to experience an otherwise two-dimensional object in action. While ballet costumes have historically drawn from either period or contemporary fashion, no company provides a better case study for the relationship between costume and high fashion than the Ballet Russes.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the Ballet Russes represented the most significant collaboration of Russian and European artists, composers, and choreographers in dance history. The impact of the company’s extraordinary synthesis of creativity is still visible in contemporary dance technique and costume design; most of the repertoire premiered by the Ballet Russes is still performed to great acclaim, while new costume designs draw heavily upon the originals.

The sets and costumes of the Ballet Russes were nothing short of sensational; the designers’ use of lavish fabrics and attention to details created spectacle and encouraged experimentation in everyday style. The most spectacular of these costumes were the work of Léon Bakst, the set and costume designer for many of the Ballet Russes’ major successful works including Schéhérazade (1910) and The Firebird (1910). It was with these influential works that the dance company revolutionized ballet by bringing the arts together in a glorious spectacle that inspired an international public as well as fashion designers, most notably the Parisian atelier, Paul Poiret.

Poiret recognized the appeal of the bacchanalian spectacle of the Ballet Russes and seized the opportunity to encourage a new Oriental aesthetic in fashion based upon the sensuous nature of the body in motion. Poiret’s designs were considered avant-garde previous to the arrival of the ballet company in Paris – he was the first fashion designer to implement Oriental style outside of a theatrical context – yet his inclinations were inspired by Bakst’s exquisite designs and encouraged by the monumental success of the Ballet Russes. Fashion scholars Valerie Mendes and Amy de la Haye agree,

"The claims of this gifted self-publicist to have been personally responsible for liberating women from the tyranny of corsets and to have been the first designer to employ bright strong colors have to be treated with caution. On the wave of a trend for Orientalism, the transition from pale to violent hues was inevitable" (Mendes and de la Haye, 32).

It was Bakst who began this trend for Orientalism, thus his costumes and sets for Ballet Russes were the true point of origin for the experience of Orientalism in fashion.

The Orient and “Orientalism”

In his luminary text, Orientalism, Edward Said sets forth the parameters by which we can define this problematic term, describing Orientalism as “the corporate institution for dealing with the Orient… by making statements about it, authorizing views of it, describing it, settling it, ruling over it: in short Orientalism [is] a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient" (Said, 3). For the purposes of my research, the peculiar entity of the Orient can be viewed as a European construct for the sake of self-definition – a shadow of the civilized West, the East was promoted and accepted as a backward and barbaric land to be conquered. As a result of this projection, European culture “gained in strength and identity by setting itself off against the Orient as a sort of surrogate and even underground self" (Said, 3). The fact that one had to travel great distances to reach the East only added to its mystique. Inaccessible to all but military personnel and merchants, the concept of the mysterious Orient was thus preserved for the majority of Westerners, reduced to little but a pipe dream for artists and armchair travelers. Tales of Eastern monsters and marvels were propagated through Western art and literature, “creating a tradition of thought, imagery, and vocabulary that have given [the East] reality and presence in and for the West” (Said, 5).

This tradition of thought in fashion began in antiquity with the exchange of valuable materials along the complex network of routes from China to the Mediterranean known as the Silk Road, and later exploded with the organization of nautical trading corporations such as the Dutch and British East India Companies. From the sixteenth to early nineteenth century, European trading companies imported a vast amount of material goods, spices and precious textiles from Asia; these were not only an indicator of Western wealth and dominance, they were the most visible evidence of Eastern presence in Western culture. The East was a place for Western exploration and domination, not the other way around. Thus the majority of Westerners understood the East through the subjective medium of visual representation in fashion and art. This explains the immediate Western association of certain patterns, dyes, materials and garments with Eastern or Oriental culture.

Henceforth, the terms “Eastern” and “Oriental” will be used interchangeably. My research makes the assumption that fashion during the early nineteenth century was a Western phenomenon. For the sake of accurately describing the appropriation of Eastern elements of style by Western artists and fashion designers, it is necessary to view these styles as their contemporary audiences did, without distinction between the geographical entity of the East and the imaginary Orient.

Léon Bakst and the Ballet Russes

Léon Bakst’s stage designs began as detailed sketches and watercolors. Previous to his work as a decorative artist with the Ballet Russes, he was a portrait painter and friend of Sergei Diaghilev, the Russian impresario who founded the Ballet Russes. At the time Diaghilev published a monthly Russian journal entitled World of Art and employed Bakst as an illustrator. Bakst specialized in portraiture and used a mix of watercolors, pastels, and gouache. His illustrations are highly stylized with a great emphasis on the shape of the body and the movement of the fabric, and the costume designs translated well to the performers’ bodies due to the materials, ornaments, and bold colors he selected. Bakst’s designs were frequently risqué, but he did not expose the body merely for theatrical effect – he felt that the artistry of the nude body had been forgotten under the cumbersome affects of nineteenth century social and theatrical dress. Dancers could not move freely in the fashionable attire of the day, and Bakst wanted to draw attention to the dynamic choreography of the Ballet Russes’ principle stars, Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina.

In a sketch for the costume of the Blue Sultana in Schéhérazade, the figure appears entirely nude under airy silk harem pants adorned with delicate patterns (Fig. 1). A diamond motif shifts across the sheer fabric below decorative embellishments at the knee. The high waist of the pants emphasizes her hourglass shape, while a generous turban balances her graceful pose. These illustrations communicated a very specific artistic idea to the seamstresses who executed the designs, making the finished product uniquely Bakst’s. In her biography of the artist, Elizabeth Ingles writes, "Bakst was endowed with a singular gift in designing costumes. Somehow the actual fabric, and the way it was cut and draped, had the subtle effect of encouraging the dancer’s movements to fit the setting or period depicted in the ballet" (Ingles, 89).

Figure 1: Léon Bakst, costume design for the Blue Sultana from Schéhérazade, 1910. Watercolor and pencil on paper. Private Collection.

Bakst’s sensual designs “amazed audiences with magnificence of color, tactility of form and the ability to both vest and expose the primordial energy of the human body… from the first Paris season [he was] an arbiter of taste in the ballet, fashion, and even interior design” (Bowlt, 104). His international success as an artist began with one of the most successful Ballet Russes productions, Schéhérazade, performed at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris c. 1910.

Schéhérazade

The story of Schéhérazade comes from the popular collection of Eastern tales, The Thousand and One Nights, an assemblage of exotic fables and fairytales featuring a colorful cast of sultans, courtesans, and sorcerers. The book made its first appearance in Europe in the eighteenth century, and though it was by no means an accurate reflection of Eastern values, it was hugely popular in Western culture. The scandalous stories of barbaric warriors and sultry odalisques fueled the Orientalist fetish in art and literature. Schéhérazade is the narrator and heroine of The Thousand and One Nights; she spins a series of complicated stories in order to entertain her murderous sultan husband and eventually wins his heart.

Bakst’s designs featured rich and unusual color combinations; at a time when pastels were in vogue he chose to draw from a palette of deep blues, greens and reds. Bakst knew the effect that these colors would have on the audience. He wrote: "I have often noticed that in each color of the prism there exists a gradation, which sometimes expresses frankness, and chastity, sometimes sensuality and even bestiality, sometimes pride, sometimes despair. This can be felt and given over to the public by the effect one makes of the various shadings. That is what I tried to do in Schéhérazade. Against a lugubrious green I put a blue full of despair, paradoxical as it may seem" (Bowlt, 104).

Indeed, the colors succeeded in creating a luxurious effect, as well as a craze for “bold, sensuous color, geometrical and concentric patterns, and richly textured fabrics" (Spencer, 180). Poiret began to use deeper colors in his designs as well, which promoted a shift in décor and fashion from the popular airy pastels of the time to a sultry palette of richer hues. Poiret also opened an interior decorating business in 1912 called Atelier Martine, which “recreated Bakstian color ensembles and oriental motifs – divans, mountains of cushions, carpets, drapes and tasseled lamps. His perfumery, Rosine, further exploited the theme with names like Maharajah, Minaret, and Borgia” (Spencer, 175).

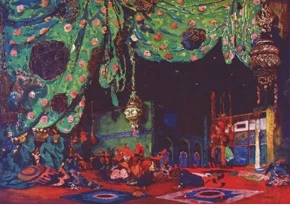

These Orientalist decorations and accessories were certainly inspired by Bakst’s set designs for Schéhérazade, which featured a vast canopy of billowing green fabric, resplendent with deep blue rosettes and decorated with golden glass beads (Fig. 2). Floor cushions and magnificent rugs littered the stage, while ornamented brass chandeliers hung from above. Not surprisingly, a similar scene could be found at the House of Poiret – renowned fashion photographer Cecil Beaton remarked: "To enter Poiret’s salons in the Faubourg St Honoré was to step into the world of the Arabian Nights. Here in rooms strewn with floor cushions, the master dressed his slaves in furs and brocades and created Eastern ladies who were the counterpart of the Cyprians and chief eunuchs that moved through the pageantries of Diaghilev" (Wilcox, 65).

Figure 2: Léon Bakst, Setting for Schéhérazade, 1910. Paper, watercolour, gouache and gold on paper, 54.5x76 cm, Musée des Arts Decoratifs, Paris.

At Poiret’s famous 1911 soirée, The Thousand and Second Night, guests “lounged on antique carpets drinking sherbet and watching semi-naked dancers, amid a mass of silks, jewels and aigrettes that sparkled iridescently like stained glass in moonlight" (Wilcox, 65).

A key historical event in the staging of the fashion spectacle, The Thousand and Second Night was no doubt influenced by the successful premiere of Schéhérazade the year before, and the Parisian public’s revelation in their fantasy of Oriental culture. Poiret’s vision benefitted from the association with the fashionable Ballet Russes, but the similarity in style did not stop there. Previous to the Ballet Russes performance Poiret was credited with redefining the fashionable silhouette of the early twentieth century. He banished corsets in favor of empire waistlines and flowing tunics, and popularized “Indian” turbans and oversized “Chinese” opera coats. The Oriental style of Bakst’s designs resonated well with Poiret’s aesthetic, giving it an additional frisson by association (Wilcox, 64). Poiret’s empire-waisted gowns and tunics emulated the aesthetic of Bakst’s costumes for Schéhérazade, making them immediately popular among the fashionable Parisian public.

The rich embroidery and dynamic shape of Nijnsky’s costume as the Golden Slave must have been a sight to behold for the first audiences of Schéhérazade (Fig. 3). An elaborate bustier of gems, beads and pearls created a dazzling effect when paired with flowing harem pants. His ensemble was topped with a colorful turban and long earrings – even his ballet slippers were adorned with rich embroidery. The overall impression was that of a hedonistic foreigner whose dress reflected none of the gender constructions of the time. The organic shapes and proliferation of designs in Nijinsky’s costumes made him appear dangerously feminine, adding another level to his Oriental otherness. The other principles and corps de ballet were sheathed in prosaic silks, and wore nude body stockings to promote the scandalous impression that they were not fully clothed (Woodcock, 143).

Figure 3: Vaslav Nijinsky as the Golden Slave from Schéhérazade, 1910. Photography by Bert. V&A: Theatre & Performance Collections, THM/165.

Poiret’s subsequent designs drew inspiration from these scantily clad dancers, incorporating sheer silks, rich colors, and exotic turbans (Fig. 4). With the success of the Ballet Russes and the enthusiasm of the Parisian public, Poiret would continue to borrow from the Bakst’s costume design for exotic effect.

Figure 4: ‘Chez Poiret,’ cover for Les Modes (April Issue, 1912) by George Barbier, 1911. Illustration of guests at the Thousand and Second Night party in Poiret’s famous garden.

The Firebird

The Firebird is based on a Russian fairytale about a prince that falls in love with a princess who has been imprisoned by the wicked sorcerer, Katschei. Prince Igor encounters the Firebird in an enchanted garden and tries to catch her, but she escapes, leaving only a feather behind. Later, she returns to save Prince Igor and all of Katschei’s prisoners, and the prince and princess live happily ever after.

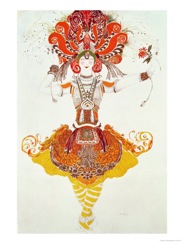

In his comprehensive text, 101 Stories of the Great Ballets, George Balanchine (a former member of Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes and the father of the New York City Ballet) describes the Firebird as a magnificent being: "Bright, glorious, and triumphant... her entrance is as strong and brilliant as the bright red she wears... Her arms and shoulders are speckled with gold dust and the shimmering red bodice reflects spangles of brilliance about her moving form... the Firebird refuses to be earth-bound and seems to resist nature by performing dashing movements that whip the very air about her" (Balanchine, 172-173).

Bakst’s designs were equally fantastic. In his sketches, the Firebird wears an enormous headdress with gold embroidery and a crown of feathers. Her long braids acknowledge the Russian heritage of the story, and her silks and gold wrist cuffs are distinctly Oriental. The Firebird also wears cropped golden pants with pointed shoes that are reminiscent of Oriental style (Fig. 5). Prince Igor wears a deep purple kaftan over trousers with tall red boots and a heavily decorated scabbard. His kaftan is evidence of his Russian origin, while the superfluous floral ornamentation of his dress creates an impression of Oriental style (Fig. 6). Bakst’s Ottoman-inspired designs are an accurate if fantastical reflection of Russia’s national identity as part of the Far East, yet they are still an Orientalist representation of Russian culture. To an early twentieth century Parisian audience, the Russian Orthodox floral motifs and silhouettes of The Firebird were just as exotic as their Middle-Eastern counterparts in Schéhérazade. This worked in the favor of the Ballet Russes, who were able to exoticize themselves because of their Russian nationality.

Figure 5: Léon Bakst, costume design for The Firebird, 1910. Gouache and gold paint. 68.5x49 cm. Private Collection.

Figure 6: Léon Bakst, costume design for Prince Igor from The Firebird, 1910. Gouache, 68.5x49 cm. Private Collection.

Floral motifs and geometrical patters were also popular in Paul Poiret’s designs, as was the style of wearing tunics over harem pants. His “lampshade” tunics look very similar to the triangular shape of Prince Igor’s costume in The Firebird, and are similarly adorned (Fig.7). Poiret’s luxurious furs and abundant jewelry also convey a sense of Russia and the Far East, drawing again on the style of Léon Bakst and the Ballet Russes.

Figure 7: Paul Poiret, “Fancy dress costume,” 1911. Seafoam green silk gauze, silver lamé, blue, silver, coral, pink and turquoise cellulose beading; L. (a) 50.25 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bakst and Poiret shared a common Parisian audience, as well as their role of stylist for Ballet Russes stars such as Tamara Karsavina. In 1914, Poiret designed an ensemble for the ballerina with a concentric circle motif, flowing sleeves and feathered turban (Fig. 8). This style was not only an extension of her Oriental stage personas, but also a reflection of the contemporary trends in patterns and fabrics. In dressing a celebrity of her status, Poiret must have drawn inspiration from her stage costumes in the years before, costumes designed by Léon Bakst.

Figure 8: Tamara Karsavina wearing a dress by Paul Poiret c. 1914. V&A: Theatre & Performance Collections.

Orientalism in Fashion Today

The popularity of Orientalism in fashion has only increased since Bakst’s designs first graced the stage in 1910. Since the early 1900’s there have been several revivals of Oriental style in stage costume as well as everyday dress. In the 1970’s David Bowie incorporated elements of Eastern style in his performances as Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane. The dynamic shapes androgynous look of traditional Eastern articles of clothing such as the tunic, harem pant, and kimono makes them particularly useful in creating a sense of the avant-garde. Because of their Oriental origin as perceived by Western culture, these garments are eternally new and always at the edge of fashion. The fact that Eastern cultures no longer wear such garments only serves to push them further into the realm of imaginary Orient. Loose-fitting harem pants in various rich colors and patterns can now be found at fast fashion outlets like Urban Outfitters, and the tunic remains a staple of casual attire. The turban is in again in vogue – a recent launch party at Très Chic showcased a collection of hand painted leather headpieces by my colleague, Katia Kull. Fashion’s fascination with the Orient is far from over, and it is more important than ever to research the origins of Oriental trends that continue to surface in everyday dress.

Conclusion

In the study of fashion history, it is easy to overlook visual artists who neither create garments nor market them under a brand name. At the same time, it is easy to see why a fashion designer and shrewd businessman like Paul Poiret might get the majority of the credit for introducing Oriental elements into high fashion. My evidence shows that Léon Bakst’s opulent, body-worshipping designs for the Ballet Russes inspired scandal and sensation, and encouraged Paul Poiret to assimilate Oriental style in high fashion. The ballet was a highly effective medium in translating stage costume to high fashion, as it was a major source of entertainment for the Parisian audience of the early twentieth century. Bakst’s designs were not only extravagantly beautiful – they also allowed the dancers of the Ballet Russes the freedom of motion required to execute their revolutionary choreography. The beauty of the body in motion in combination with Bakst’s sensuous Oriental costumes and set designs caused a shift in fashion toward the exotic. Paul Poiret capitalized on this trend by borrowing his ideas from Bakst, popularizing the dramatic Oriental silhouettes, geometric patterns, and rich colors that he witnessed at the Ballet Russes performances of Schéhérazade and The Firebird. Thus the work of Léon Bakst is central to our understanding of Orientalism in fashion, as his designs for the Ballet Russes were and continue to be a source of inspiration for countless artists to date.

Bibliography

Balanchine, George and Francis Mason. 101 Stories of the Great Ballets. New York: Anchor Books, 1989.

Bowlt, John E. “Léon Bakst, Natalia Goncharova, and Pablo Picasso,” in Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes 1909-1929, edited by Jane Pritchard, 104-119. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 2013.

Ingles, Elisabeth. Bakst. London: Parkstone Press, 2000.

Mendes, Valerie and Amy de la Haye. 20th Century Fashion. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999.

Pruzhan, Irina. Léon Bakst, Set and Costume Designs, Book Illustrations, Paintings and Graphic Works. Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1986.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

Spencer, Charles. Léon Bakst and the Ballet Russes. London: Academy Editions, 1995.

The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. “Fancy dress costume, 1911.” Accessed October 26, 2013. http://www.metmuseum.org.

Wilcox, Claire. “Paul Poiret and the Ballet Russes,” in Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes 1909-1929, edited by Jane Pritchard, 64-65. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 2013.

Woodcock, Sarah. “Wardrobe,” in Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes 1909-1929, edited by Jane Pritchard, 128-163. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 2013.